Psycho (1960) Directed by: Alfred Hitchcock; Written by

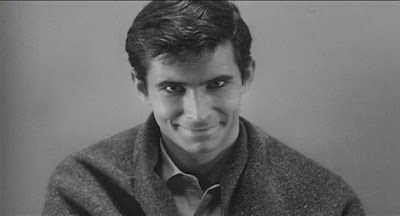

Joseph Stefano; Based on the novel by Robert Bloch; Starring: Anthony Perkins,

Janet Leigh, Vera Miles, John Gavin and Martin Balsam

Available

on Blu-ray and DVD

Rating: *****

Psycho II (1982)

Directed by: Richard Franklin; Written by Tom Holland; Based on characters by

Robert Bloch; Starring: Anthony Perkins, Meg Tilly, Vera Miles, Robert Loggia

and Dennis Franz

Available on

Blu-ray and DVD

Rating: *** ½

“The processes

through which we take the audience, you see, it’s rather like taking them

through the haunted house at the fairground or the rollercoaster, you know.” –

Alfred Hitchcock (excerpt from 1963 interview with Ian Cameron and V.F.

Perkins, Alfred Hitchcock Interviews,

edited by Peter Brunette)

“I’ve long since

tried to forget about disassociating myself with the specter of Norman Bates,

so I’ve got to give into that rather than resist it…” – Anthony Perkins

(excerpt from 1983 interview with Bobbie Wygant)

I’m thrilled to

be a part of Hitchcock Halloween, a tribute to cinema’s undisputed master of

suspense, sponsored by Lara at Backlots. Be sure to check out her site for a comprehensive

list of posts and participants.

This is not a

review. Well, not in the strictest

sense. Double Take is less of an

analysis, and more of a gut reaction to two films, compared side by side: original

and remake, or in this case, original film and sequel. Psycho

has been discussed, picked apart, and scrutinized to death over the years, so a

traditional review of the film covering the same scenes, lines and themes seems

almost pointless. Instead, I’d rather

address my initial reaction to Psycho

and its belated sequel.

My first (partial)

exposure to Psycho was as a kid,

sometime in the late 70s. Although I don’t

recall the exact program, the infamous shower scene was featured on a TV

retrospective of scary scenes. Although

I didn’t watch the scene in its proper context until several years later,

Hitchcock’s iconic imagery was tattooed on my brain. I couldn’t shake the horror I felt as I witnessed

the sanctity of a banal bathroom hygiene ritual devolve into chaos as a woman was

brutally stabbed to death. It wasn’t the

stabbing that got to me, however, but her vulnerability, followed by a shot of

her lifeless eyes, which communicated utter betrayal. The experience was so traumatic, that I was

afraid to use the shower for weeks afterward, fearing I would meet the same

fate as Marion Crane. The scene has

since been copied and parodied so many times that its effectiveness has

probably been lost on many present-day viewers.

By the same token, this single sequence has been so closely associated

with Psycho, it’s no surprise the filmmakers of the sequel employed it as the

opening scene.

Like many

classics, Psycho was not appreciated

by critics when it was first released.

Over the ensuing years, it came to be regarded as an indispensable

paragon of the suspense/horror genre.

Unfortunately, this revisionist stance didn’t help Psycho II when it debuted 23 years later. It must have seemed like a fool’s errand to

try to follow in the footsteps of Hitchcock.

No matter how skillful the sequel was, probably no one was willing to

give it a fair shake. But director

Richard Franklin proved he was up to the task, having observed the master in

action on the set of Topaz, and demonstrating his penchant for creating

suspenseful films in his native Australia with Patrick and Road Games.

If the choice of

director for Psycho II was open for

debate, one thing that was non-negotiable was the film’s star, Anthony Perkins

as Norman Bates. 20-plus years after his

chilling portrayal of Bates, Perkins returned to play the character that had

become synonymous with his name. Looking

back, it’s impossible to imagine anyone else occupying the role he pioneered. Much of Psycho’s

creepiness could be attributed to Perkins’ quiet, unassuming demeanor, and gawky

frame. He was frightening because he

resembled the farthest thing from a monster.

As good as the

other elements needed to be in Psycho II,

the onus rested largely on the shoulders of Perkins. His portrayal of the tortured Bates was a

continuation of the original character, the likely culmination of Perkins’ ambivalence

about playing someone who defined and constricted his career. Two decades later, Bates is seen as a man

with a horrible past he’s unable to shake, eternally condemned to wrestle his

inner demons.

One of the most

obvious differences between the two films is the use of black and white versus

color. Hitchcock chose to shoot his film

in black and white when color had become the norm, as an artistic choice,

purportedly because the sight of blood in color would have been too horrible. True or not, the stark photography by John L.

Russell (accompanied by a score composer Bernard Herrmann described as “black

and white), goes a long way to weave a twisted tale. Cinematographer Dean Cundey (a veteran of

several John Carpenter films) lends atmosphere to Psycho II with his use of contrasts and angles. One memorable shot of the Bates house,

flanked by indigo sky and gray clouds, generates an overwhelming feeling of

foreboding. In another shot, as Bates’ sanity

begins to lapse, the house appears askew.

Many cynics

would argue, and not without some justification, that Psycho II exists

for no reason other than milking a cash cow for Universal Studios. While it’s a foregone conclusion that any

follow up to a Hitchcock original could never quite live up to its predecessor,

it’s selling the sequel short. Both

films are products from different eras.

During the production of Psycho,

the production code was still enforced, although Hitchcock tested the

boundaries of what could be shown. As a

result, Psycho is a masterpiece of

suggestion, tricking us into thinking we’ve seen more than we actually saw. Contrast this with the “anything goes”

filmmaking of the 80s, when Psycho II

was released. With this in mind,

Franklin shows a commendable level of restraint. Tom Holland’s screenplay, in a nod to

Hitchcock, also employs a MacGuffin (or two) to divert our attention. Is Psycho

II a perfect sequel? Not quite, but

then again, nothing could possibly live up to our inflated expectations. The true test of a good sequel is whether or not

it builds off of the original themes without trying too hard to ride the

coattails of the source material. Taken

from a perspective 30 years later (longer than the gap between the two movies),

Psycho II is an excellent, underrated

thriller in its own right, and I contend that both films can happily co-exist

on my personal video library shelf.